Lovely auroras will sweep most of Canada and parts of the northern US this weekend from a chain of solar eruptions including a “cannibal” coronal mass ejection that pounded Earth on Tuesday. This is where you should search.

An examination of the mummy, known as the “Screaming Woman,” shows that an ancient Egyptian woman died in great suffering and her muscles froze her final scream in place for 3,500 years.

Suggesting a unique approach of preservation, the researchers also discovered that the woman had all of her organs inside her body and had been embalmed in costly imported drugs.

The results were presented by the researchers in a fresh paper released Friday, August 2, in the Frontiers in Medicine journal.

Study co-author Sahar Saleem, a mummy radiologist at Kasr Al Ainy Hospital of Cairo University, emailed Live Science saying, “Mummification in ancient Egypt is still full of secrets.” Usually a symptom of poor or neglectful mummification, intact organs are rare; yet, the Screaming Woman was exceptionally well preserved.

“This surprised me since the New Kingdom’s [circa 1550 to 1070 B.C.] traditional mummification technique included the elimination of all organs except the heart,” Saleem remarked.

While excavating the tomb of Senenmut, a well-known architect and government official allegedly to be the secret lover of Queen Hatshepsut, archaeologists discovered the “Screaming Woman” body in Deir el-Bahari, near Luxor, Egypt, in 1935. Named for her gaping mouth, Interred in an adjacent funeral chamber, the Screaming Woman most certainly belonged to Senenmut’s close relatives, Saleem observed.

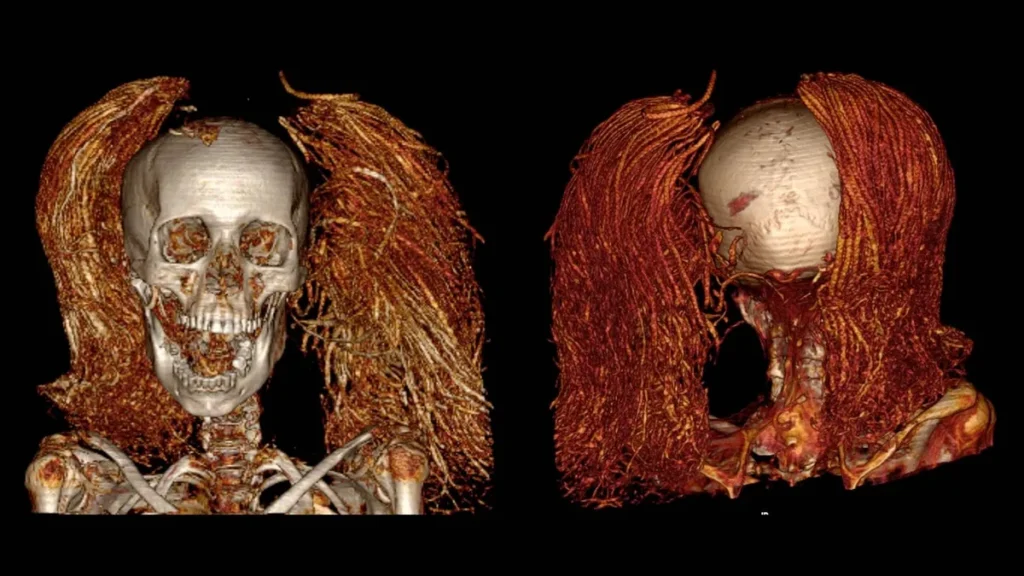

The mummy had two scarab rings and black wig. Her naturally occurring hair has been henna and juniper tinted. The wig was manufactured from date palm, according to electron microscopy; an X-ray diffraction examination revealed it had a mix of quartz, magnetite, and albite crystals, most likely to harden the locks and give her hair a black tint. Wigs were employed in daily life as well as for funerary needs.

Her extensive embalming, Saleem and research co-author Samia El-Merghani of the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, revealed perhaps the key to her preservation. Their infrared spectroscopy revealed residues of frankincense and juniper resin, luxury goods most likely brought into Egypt from the Eastern Mediterranean and East Africa or Southern Arabia. The resin and frankincense stopped the body from falling apart under the influence of microbes and insects.

Saleem observed that other mummy with a screaming expression were Prince Pentawere (1173 to 1155 B.C.) and Princess Meritamun (1525 to 1504 B.C.). Their gaping jaws caught attention.

“Opening of the mouth occurs when these muscles relax during sleeping or when they degrade after death,” Saleem explained. “Embalmers regularly wrapped the mandible around the skull to keep the dead’s mouth closed.”

This case was different, though: a terrible death caused the gaping mouth. “The mummy’s screaming facial expression in this study could be read as a cadaveric spasm, implying that the woman died screaming from agony,” Saleem said. When muscles tense just minutes before death, a condition known as cadaveric spasm results. This disorder can strike in events including drowning, suicide, or attack.

Unlike the two other mummies, Pentawere died of suicide and Meritamun of a heart attack; a computed tomography (CT) scan of the Screaming Woman did not expose her cause of death.

The CT scan’s 2D and 3D images, however, did highlight the woman’s height, age, and medical issues—that she had stood roughly 5 feet (1.5 meters). Her two pelvic bones’ joint, which changes with age, suggested that she died about 48 years old. Her spine’s bones also pointed to her perhaps having minor arthritis. Indicated by unhealed dental sockets, the woman was missing numerous teeth, most likely lost just before death.

Advances in scientific methods will hopefully allow Saleem and her colleagues to expose more information about the mummy.

“Her well-preserved body was like a time capsule enabling us to know how she lived, the diseases she suffered from, and capture her death that could be in pain,” Saleem said. “This kind of research humanizes the mummy and let us look to her as a human being.”

Her coffin and rings are on exhibit at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; the Screaming Woman resides in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.