A groundbreaking NASA robot has identified over a thousand seismic events on Mars, potentially unveiling a substantial reservoir of water beneath its surface.

Utilizing unprecedented data from the InSight lander, which meticulously recorded geological activity on Mars for four years, planetary scientists have suggested the presence of water located several miles beneath the Martian crust. This research not only invites further exploration but also offers insights into the fate of the Red Planet’s water as it dried out over time, hinting at the possibility of hospitable environments for life.

On Earth, vast reservoirs of water lie hidden beneath the surface. So, could similar conditions exist on Mars?

“Absolutely! We have pinpointed what could be considered the Martian equivalent of deep groundwater found on Earth,” stated Michael Manga, a planetary scientist at UC Berkeley and coauthor of the study, in an interview with Mashable.

This study has recently been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

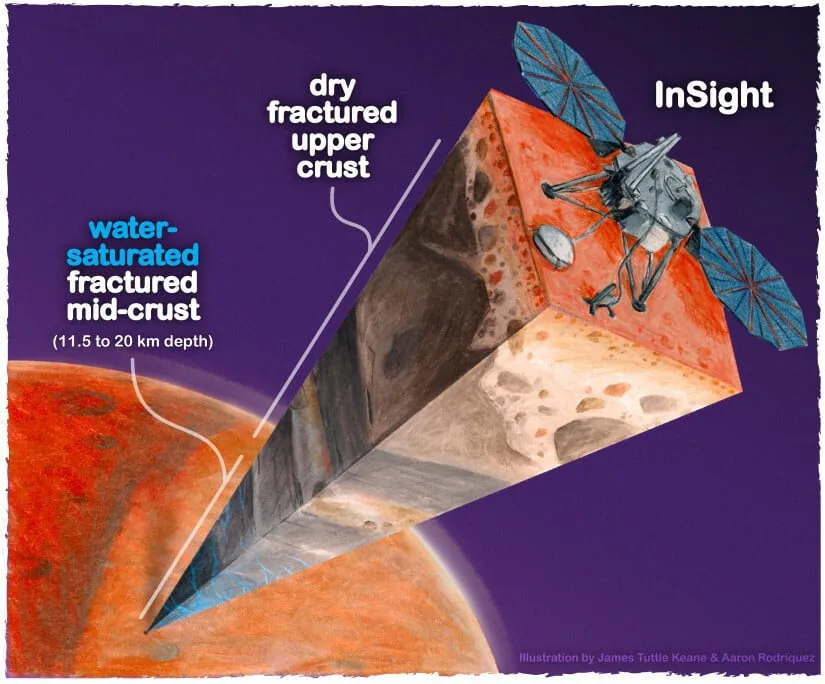

The detected water is situated far below the Martian surface, which today is approximately 1,000 times drier than Earth’s most arid deserts. It is believed to be located between seven to thirteen miles (11.5 to 20 kilometers) underground, existing within cracks and fissures in the deep Martian crust, as illustrated in the accompanying graphic.

The InSight lander was meticulously designed by NASA to probe the internal dynamics of Mars, equipped with a seismometer akin to those used to monitor earthquakes on Earth. This instrument detected various types of seismic waves generated by marsquakes, geological activity, and meteorite impacts. These waves, produced by forces such as impacts or tremors, yield critical information about the subsurface composition. The velocity of these seismic waves is influenced by the rock’s material, the presence of fractures, and the substances filling those fractures, as explained by Manga. The research team then integrated these seismic readings, along with subsurface gravity measurements, into simulation programs that model subsurface conditions—similar to the methodologies geologists employ to map water aquifers or gas deposits on Earth.

“A mid-crust characterized by cracked rocks filled with liquid water provides the best explanation for both seismic and gravity data,” Manga noted.

Historically, Mars was a temperate planet that hosted extensive lakes and rivers. Approximately 3 billion years ago, scientists theorize that much of this water was lost to space as Mars gradually shed its insulating atmosphere. However, significant quantities of water may have seeped into the subsurface as well. Although the exact amount remains uncertain, this recent detection suggests that a considerable volume of water could reside within the deep Martian crust.

“We always considered the possibility that liquid water, buried deep underground, could explain the disappearance of Mars’ ancient surface water,” Manga remarked.

The potential existence of water raises an intriguing question: Could life exist in these depths? Evidence from Earth provides a compelling parallel.

“On Earth, microbial life thrives deep underground where rocks are saturated with water and energy sources are available,” Manga explained.

Future Martian explorers may face challenges in drilling several miles into the Martian crust to access or analyze this water. However, they may discover other locations, such as geologically active areas like Cerberus Fossae, where liquid water could potentially surface.

While the Martian surface may present a harsh and irradiated environment, it remains plausible that resilient forms of life could flourish in the deep, watery underworld beneath.